How Did Franklin D Roosevelt Try To Change The Makeup Of The Supreme Court

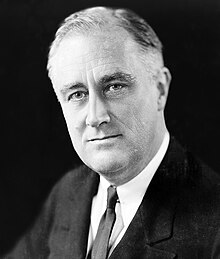

President Franklin D. Roosevelt. His dissatisfaction over Supreme Court decisions holding New Bargain programs unconstitutional prompted him to seek methods to change the way the court functioned.

The Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937,[one] ofttimes called the "court-packing plan",[2] was a legislative initiative proposed past U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to add together more than justices to the U.S. Supreme Court in society to obtain favorable rulings regarding New Bargain legislation that the Courtroom had ruled unconstitutional.[3] The fundamental provision of the bill would have granted the president ability to engage an additional justice to the U.S. Supreme Courtroom, upward to a maximum of six, for every member of the court over the age of 70 years.

In the Judiciary Human action of 1869, Congress had established that the Supreme Courtroom would consist of the chief justice and eight associate justices. During Roosevelt'due south first term, the Supreme Court struck downwards several New Deal measures as being unconstitutional. Roosevelt sought to reverse this by changing the makeup of the court through the date of new additional justices who he hoped would rule that his legislative initiatives did not exceed the ramble authority of the authorities. Since the U.South. Constitution does not define the Supreme Court's size, Roosevelt believed information technology was within the power of Congress to alter information technology. Members of both parties viewed the legislation as an attempt to stack the court, and many Democrats, including Vice President John Nance Garner, opposed it.[four] [5] The bill came to be known as Roosevelt's "court-packing plan", a phrase coined by Edward Rumely.[2]

In Nov 1936, Roosevelt won a sweeping re-ballot victory. In the months post-obit, he proposed to reorganize the federal judiciary by adding a new justice each time a justice reached historic period 70 and failed to retire.[six] The legislation was unveiled on February 5, 1937, and was the field of study of Roosevelt's 9th fireside chat on March nine, 1937.[7] [8] He asked, "Can information technology be said that total justice is achieved when a court is forced past the sheer necessity of its business to decline, without fifty-fifty an caption, to hear 87% of the cases presented by private litigants?" Publicly denying the president'south statement, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes reported, "There is no congestion of cases on our agenda. When we rose March 15 we had heard arguments in cases in which cert has been granted only iv weeks earlier. This gratifying situation has obtained for several years".[9] Three weeks later on the radio address, the Supreme Court published an opinion upholding a Washington country minimum wage law in W Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish.[10] The 5–4 ruling was the outcome of the apparently sudden jurisprudential shift by Acquaintance Justice Owen Roberts, who joined with the wing of the bench supportive to the New Bargain legislation. Since Roberts had previously ruled against well-nigh New Bargain legislation, his support here was seen as a issue of the political force per unit area the president was exerting on the court. Some interpreted Roberts' reversal as an try to maintain the Courtroom'southward judicial independence by alleviating the political pressure to create a courtroom more friendly to the New Bargain. This reversal came to be known as "the switch in fourth dimension that saved nine"; withal, recent legal-historical scholarship has called that narrative into question[xi] equally Roberts' decision and vote in the Parrish case predated both the public announcement and introduction of the 1937 pecker.[12]

Roosevelt's legislative initiative ultimately failed. Henry F. Ashurst, the Autonomous chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, held up the bill by delaying hearings in the commission, saying, "No haste, no hurry, no waste, no worry—that is the motto of this committee."[xiii] As a effect of his delaying efforts, the beak was held in committee for 165 days, and opponents of the bill credited Ashurst as instrumental in its defeat.[v] The bill was further undermined by the untimely death of its chief advocate in the U.S. Senate, Senate Majority Leader Joseph T. Robinson. Other reasons for its failure included members of Roosevelt's own Democratic Party believing the bill to be unconstitutional, with the Judiciary Committee ultimately releasing a scathing written report calling it "a needless, futile and utterly dangerous abandonment of constitutional principle ... without precedent or justification".[14] [9] Contemporary observers broadly viewed Roosevelt's initiative as political maneuvering. Its failure exposed the limits of Roosevelt's abilities to push forward legislation through direct public entreatment. Public perception of his efforts here was in stark contrast to the reception of his legislative efforts during his first term.[15] [sixteen] Roosevelt ultimately prevailed in establishing a majority on the court friendly to his New Bargain legislation, though some scholars view Roosevelt'south victory every bit pyrrhic.[sixteen]

Groundwork [edit]

New Bargain [edit]

Following the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the onset of the Bully Depression, Franklin Roosevelt won the 1932 presidential election on a promise to give America a "New Deal" to promote national economic recovery. The 1932 election also saw a new Democratic bulk sweep into both houses of Congress, giving Roosevelt legislative support for his reform platform. Both Roosevelt and the 73rd Congress chosen for greater governmental involvement in the economy every bit a mode to end the depression.[17] During the president's first term, a serial of successful challenges to various New Deal programs were launched in federal courts. Information technology soon became clear that the overall constitutionality of much of the New Deal legislation, especially that which extended the power of the federal government, would be decided past the Supreme Court.

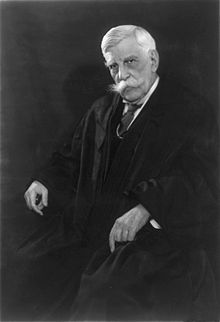

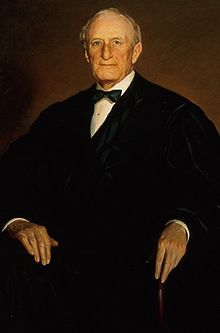

Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. Holmes's loss of half his pension pay due to New Bargain legislation subsequently his 1932 retirement is believed to have dissuaded Justices Van Devanter and Sutherland from parting the bench.

A pocket-size aspect of Roosevelt's New Deal agenda may have itself directly precipitated the showdown between the Roosevelt administration and the Supreme Court. Shortly after Roosevelt's inauguration, Congress passed the Economy Act, a provision of which cut many government salaries, including the pensions of retired Supreme Court justices. Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who had retired in 1932, saw his pension halved from $xx,000 to $ten,000 per yr.[xviii] The cutting to their pensions appears to have dissuaded at least two older Justices, Willis Van Devanter and George Sutherland, from retirement.[19] Both would later on detect many aspects of the New Bargain unconstitutional.

Roosevelt's Justice Department [edit]

The flurry of new laws in the wake of Roosevelt's start hundred days swamped the Justice Department with more responsibilities than it could manage.[20] Many Justice Department lawyers were ideologically opposed to the New Bargain and failed to influence either the drafting or review of much of the White Firm's New Deal legislation.[21] The ensuing struggle over ideological identity increased the ineffectiveness of the Justice Section. As Interior Secretary Harold Ickes complained, Attorney General Homer Cummings had "simply loaded it [the Justice Section] with political appointees" at a time when information technology would exist responsible for litigating the flood of cases arising from New Deal legal challenges.[22]

Compounding matters, Roosevelt's congenial Solicitor General, James Crawford Biggs (a patronage appointment chosen by Cummings), proved to be an ineffective advocate for the legislative initiatives of the New Deal.[23] While Biggs resigned in early 1935, his successor Stanley Forman Reed proved to exist little better.[twenty]

This disarray at the Justice Department meant that the government'south lawyers ofttimes failed to foster feasible test cases and arguments for their defence, later handicapping them before the courts.[21] As Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes would afterwards note, it was considering much of the New Deal legislation was so poorly drafted and defended that the court did not uphold information technology.[21]

Jurisprudential context [edit]

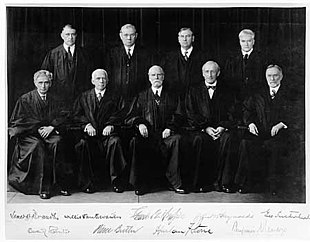

Popular understanding of the Hughes Courtroom, which has some scholarly support,[ who? ] has typically cast it as divided between a conservative and liberal faction, with 2 critical swing votes. The conservative Justices Pierce Butler, James Clark McReynolds, George Sutherland and Willis Van Devanter were known every bit "The Four Horsemen". Opposed to them were the liberal Justices Louis Brandeis, Benjamin Cardozo and Harlan Fiske Stone, dubbed "The 3 Musketeers". Master Justice Charles Evans Hughes and Justice Owen Roberts were regarded as the swing votes on the court.[24] Some recent scholarship has eschewed these labels since they suggest more legislative, every bit opposed to judicial, differences. While it is true that many rulings of the 1930s Supreme Court were deeply divided, with four justices on each side and Justice Roberts equally the typical swing vote, the ideological divide this represented was linked to a larger argue in U.S. jurisprudence regarding the role of the judiciary, the pregnant of the Constitution, and the respective rights and prerogatives of the different branches of authorities in shaping the judicial outlook of the Court. At the same fourth dimension, still, the perception of a conservative/liberal divide does reflect the ideological leanings of the justices themselves. As William Leuchtenburg has observed:

Some scholars disapprove of the terms "conservative" and "liberal", or "right, center, and left", when applied to judges because information technology may suggest that they are no dissimilar from legislators; just the individual correspondence of members of the Court makes clear that they idea of themselves as ideological warriors. In the autumn of 1929, Taft had written i of the Iv Horsemen, Justice Butler, that his well-nigh fervent promise was for "connected life of enough of the present membership ... to prevent disastrous reversals of our present mental attitude. With Van [Devanter] and Mac [McReynolds] and Sutherland and you and Sanford, at that place will be 5 to steady the boat ..."[25]

Whatever the political differences among the justices, the clash over the constitutionality of the New Bargain initiatives was tied to clearly divergent legal philosophies which were gradually coming into competition with each other: legal formalism and legal realism.[26] During the period c. 1900 – c. 1920, the formalist and realist camps clashed over the nature and legitimacy of judicial authority in common law, given the lack of a central, governing potency in those legal fields other than the precedent established by case law—i.e. the amass of earlier judicial decisions.[26]

This fence spilled over into the realm of constitutional law.[26] Realist legal scholars and judges argued that the constitution should be interpreted flexibly and judges should not apply the Constitution to impede legislative experimentation. Ane of the most famous proponents of this concept, known as the Living Constitution, was U.Due south. Supreme Courtroom justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who said in Missouri v. Holland the "case earlier us must exist considered in the light of our whole feel and not merely in that of what was said a hundred years agone".[27] [28] The conflict between formalists and realists implicated a changing but however-persistent view of ramble jurisprudence which viewed the U.S. Constitution as a static, universal, and general certificate not designed to change over fourth dimension. Under this judicial philosophy, case resolution required a simple restatement of the applicative principles which were then extended to a case'due south facts in order to resolve the controversy.[29] This earlier judicial mental attitude came into direct conflict with the legislative accomplish of much of Roosevelt'due south New Deal legislation. Examples of these judicial principles include:

- the early-American fear of centralized dominance which necessitated an unequivocal stardom between national powers and reserved state powers;

- the clear delineation between public and private spheres of commercial activity susceptible to legislative regulation; and

- the respective separation of public and private contractual interactions based upon "gratis labor" ideology and Lockean property rights.[30]

At the same time, developing modernist ideas regarding politics and the role of government placed the part of the judiciary into flux. The courts were mostly moving away from what has been chosen "guardian review" — in which judges dedicated the line betwixt appropriate legislative advances and majoritarian encroachments into the individual sphere of life—toward a position of "bifurcated review". This arroyo favored sorting laws into categories that demanded deference towards other branches of government in the economic sphere, but aggressively heightened judicial scrutiny with respect to cardinal civil and political liberties.[31] The slow transformation away from the "guardian review" role of the judiciary brought about the ideological—and, to a caste, generational—rift in the 1930s judiciary. With the Judiciary Neb, Roosevelt sought to accelerate this judicial evolution by diminishing the dominance of an older generation of judges who remained fastened to an earlier manner of American jurisprudence.[30] [32]

New Deal in courtroom [edit]

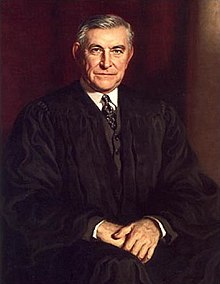

Associate Justice Owen J. Roberts. The balance of the Supreme Court in 1935 caused the Roosevelt administration much business concern over how Roberts would adjudicate New Deal challenges.

Roosevelt was wary of the Supreme Court early on in his kickoff term, and his administration was slow to bring constitutional challenges of New Deal legislation before the court.[33] All the same, early wins for New Bargain supporters came in Home Building & Loan Association 5. Blaisdell [34] and Nebbia v. New York [35] at the start of 1934. At issue in each case were state laws relating to economic regulation. Blaisdell concerned the temporary suspension of creditor's remedies by Minnesota in order to combat mortgage foreclosures, finding that temporal relief did not, in fact, impair the obligation of a contract. Nebbia held that New York could implement price controls on milk, in accordance with the country'south police power. While not tests of New Deal legislation themselves, the cases gave cause for relief of administration concerns about Associate Justice Owen Roberts, who voted with the majority in both cases.[36] Roberts's opinion for the court in Nebbia was also encouraging for the administration:[33]

[T]his courtroom from the early days affirmed that the power to promote the general welfare is inherent in government.[37]

Nebbia also holds a particular significance: information technology was the one case in which the Court abandoned its jurisprudential stardom between the "public" and "private" spheres of economic action, an essential distinction in the court'southward analysis of state police power.[32] The effect of this decision radiated outward, affecting other doctrinal methods of assay in wage regulation, labor, and the power of the U.S. Congress to regulate commerce.[xxx] [32]

Black Mon [edit]

Just three weeks afterward its defeat in the railroad pension example, the Roosevelt administration suffered its almost astringent setback, on May 27, 1935: "Blackness Monday".[38] Chief Justice Hughes arranged for the decisions announced from the bench that mean solar day to be read in order of increasing importance.[38] The Supreme Court ruled unanimously against Roosevelt in 3 cases:[39] Humphrey's Executor five. United States, Louisville Articulation Stock Land Bank 5. Radford, and Schechter Poultry Corp. 5. United States.

Further New Deal setbacks [edit]

Chaser General Homer Stillé Cummings. His failure to prevent poorly-drafted New Deal legislation from reaching Congress is considered his greatest shortcoming as Attorney General.[21]

With several cases laying forth the criteria necessary to respect the due process and property rights of individuals, and statements of what constituted an appropriate delegation of legislative powers to the President, Congress speedily revised the Agricultural Adjustment Deed (AAA).[40] However, New Deal supporters still wondered how the AAA would fare against Chief Justice Hughes's restrictive view of the Commerce Clause from the Schechter determination.

Antecedents to reform legislation [edit]

Associate Justice James Clark McReynolds. A legal opinion authored by McReynolds in 1914, while U.South. Chaser General, is the near probable source for Roosevelt's courtroom reform plan.

The coming disharmonize with the court was foreshadowed past a 1932 campaign statement Roosevelt made:

Afterward March 4, 1929, the Republican party was in complete control of all branches of the government—the legislature, with the Senate and Congress; and the executive departments; and I may add together, for full mensurate, to make information technology complete, the The states Supreme Court besides.[41]

An April 1933 letter of the alphabet to the president offered the thought of packing the Courtroom: "If the Supreme Court's membership could be increased to twelve, without too much trouble, perchance the Constitution would be found to be quite elastic."[41] The adjacent month, soon-to-be Republican National Chairman Henry P. Fletcher expressed his concern: "[A]due north administration as fully in command as this one tin can pack it [the Supreme Courtroom] every bit easily as an English language government can pack the Business firm of Lords."[41]

Searching out solutions [edit]

Every bit early as the autumn 1933, Roosevelt had begun anticipation of reforming a federal judiciary composed of a stark majority of Republican appointees at all levels.[42] Roosevelt tasked Attorney Full general Homer Cummings with a year-long "legislative project of neat importance".[43] Justice Department lawyers then commenced enquiry on the "secret project", with Cummings devoting what time he could.[43] The focus of the research was directed at restricting or removing the Supreme Court's power of judicial review.[43] Still, an autumn 1935 Gallup Poll had returned a majority disapproval of attempts to limit the Supreme Court's power to declare acts unconstitutional.[44] For the time being, Roosevelt stepped back to lookout man and await.[45]

Other alternatives were also sought: Roosevelt inquired nigh the rate at which the Supreme Court denied certiorari, hoping to attack the Courtroom for the small number of cases it heard annually. He too asked almost the case of Ex parte McCardle, which express the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, wondering if Congress could strip the Court's power to adjudicate ramble questions.[43] The span of possible options fifty-fifty included constitutional amendments; however, Roosevelt soured to this idea, citing the requirement of iii-fourths of state legislatures needed to ratify, and that an opposition wealthy enough could too hands defeat an amendment.[46] Farther, Roosevelt deemed the subpoena process in itself too deadening when fourth dimension was a deficient commodity.[47]

Unexpected answer [edit]

Attorney General Cummings received novel advice from Princeton University professor Edward S. Corwin in a letter of December 16, 1936. Corwin had relayed an idea from Harvard University professor Arthur Northward. Holcombe, suggesting that Cummings tie the size of the Supreme Court's bench to the age of the justices since the pop view of the Court was critical of their age.[48] All the same, another related idea fortuitously presented itself to Cummings as he and his assistant Carl McFarland were finishing their collaborative history of the Justice Department, Federal justice: chapters in the history of justice and the Federal executive. An opinion written by Associate Justice McReynolds—i of Cumming'southward predecessors equally Chaser Full general, nether Woodrow Wilson—had made a proposal in 1914 which was highly relevant to Roosevelt's electric current Supreme Courtroom troubles:

Judges of the The states Courts, at the age of 70, after having served x years, may retire upon total pay. In the past, many judges have availed themselves of this privilege. Some, however, have remained upon the bench long beyond the time that they are able to adequately belch their duties, and in issue the administration of justice has suffered. I suggest an act providing that when any judge of a federal court beneath the Supreme Courtroom fails to avail himself of the privilege of retiring now granted past law, that the President be required, with the advice and consent of the Senate, to appoint another judge, who would preside over the diplomacy of the courtroom and have precedence over the older one. This will insure at all times the presence of a estimate sufficiently active to discharge promptly and fairly the duties of the courtroom.[49]

The content of McReynolds's proposal and the bill later submitted past Roosevelt were so similar to each other that information technology is thought the nearly probable source of the idea.[50] Roosevelt and Cummings also relished the opportunity to hoist McReynolds by his own petard.[51] McReynolds, having been born in 1862,[52] had been in his early fifties when he wrote his 1914 proposal, merely was well over 70 when Roosevelt's plan was set up forth.

Reform legislation [edit]

Contents [edit]

The provisions of the bill adhered to iv central principles:

- allowing the President to appoint 1 new, younger gauge for each federal approximate with 10 years service who did non retire or resign within 6 months after reaching the age of 70 years;

- limitations upon the number of judges the President could engage: no more than six Supreme Courtroom justices, and no more than than two on any lower federal court, with a maximum allocation betwixt the ii of 50 new judges but after the pecker is passed into law;

- that lower-level judges be able to bladder, roving to district courts with exceptionally busy or backlogged dockets; and

- lower courts exist administered by the Supreme Courtroom through newly created "proctors".[53]

The latter provisions were the result of lobbying by the energetic and reformist judge William Denman of the Ninth Circuit Court who believed the lower courts were in a state of disarray and that unnecessary delays were affecting the appropriate administration of justice.[54] [55] Roosevelt and Cummings authored accompanying messages to transport to Congress along with the proposed legislation, hoping to couch the fence in terms of the need for judicial efficiency and relieving the backlogged workload of elderly judges.[56]

The pick of date on which to launch the programme was largely determined by other events taking place. Roosevelt wanted to present the legislation before the Supreme Court began hearing oral arguments on the Wagner Act cases, scheduled to begin on February eight, 1937; however, Roosevelt also did not want to present the legislation before the annual White House dinner for the Supreme Court, scheduled for February 2.[57] With a Senate recess betwixt February 3–v, and the weekend falling on February 6–vii, Roosevelt had to settle for Feb five.[57] Other pragmatic concerns likewise intervened. The administration wanted to introduce the bill early enough in the Congressional session to brand sure it passed before the summer recess, and, if successful, to get out time for nominations to any newly created bench seats.[57]

Public reaction [edit]

After the proposed legislation was announced, public reaction was split. Since the Supreme Court was generally conflated with the U.S. Constitution itself,[58] the proposal to change the Court brushed up against this wider public reverence.[59] Roosevelt's personal involvement in selling the program managed to mitigate this hostility. In a Democratic Victory Dinner speech on March 4, Roosevelt called for political party loyalists to support his plan.

Roosevelt followed this upwards with his ninth Fireside conversation on March ix, in which he made his case directly to the public. In his address, Roosevelt decried the Supreme Court'south bulk for "reading into the Constitution words and implications which are non there, and which were never intended to be there".[60] He also argued directly that the Beak was needed to overcome the Supreme Court'due south opposition to the New Deal, stating that the nation had reached a indicate where it "must accept activeness to relieve the Constitution from the Court, and the Court from itself".[60]

Through these interventions, Roosevelt managed briefly to earn favorable press for his proposal.[61] In general, nonetheless, the overall tenor of reaction in the press was negative. A series of Gallup Polls conducted between February and May 1937 showed that the public opposed the proposed bill by a fluctuating majority. By belatedly March it had become clear that the President's personal abilities to sell his plan were limited:

Over the entire period, back up averaged about 39%. Opposition to Court packing ranged from a low of 41% on 24 March to a high of 49% on 3 March. On boilerplate, about 46% of each sample indicated opposition to President Roosevelt's proposed legislation. And it is articulate that, afterwards a surge from an early push by FDR, the public back up for restructuring the Court rapidly melted.[62]

Concerted letter-writing campaigns to Congress against the bill were launched with stance tallying against the bill nine-to-one. Bar associations nationwide followed suit besides lining upwards in opposition to the bill.[63] Roosevelt's own Vice President John Nance Garner expressed disapproval of the bill belongings his olfactory organ and giving thumbs down from the rear of the Senate chamber.[64] The editorialist William Allen White characterized Roosevelt's actions in a column on February six as an "elaborate stage play to flatter the people by a simulation of frankness while denying Americans their autonomous rights and discussions by suave abstention—these are not the traits of a democratic leader".[65]

Reaction against the neb also spawned the National Committee to Uphold Constitutional Government, which was launched in February 1937 by three leading opponents of the New Deal. Frank E. Gannett, a newspaper magnate, provided both money and publicity. Ii other founders, Amos Pinchot, a prominent lawyer from New York, and Edward Rumely, a political activist, had both been Roosevelt supporters who had soured on the President's calendar. Rumely directed an effective and intensive mailing campaign to pulsate upwardly public opposition to the measure out. Among the original members of the Commission were James Truslow Adams, Charles Coburn, John Haynes Holmes, Dorothy Thompson, Samuel S. McClure, Mary Dimmick Harrison, and Frank A. Vanderlip. The Committee'southward membership reflected the bipartisan opposition to the bill, particularly among amend educated and wealthier constituencies.[66] As Gannett explained, "nosotros were conscientious not to include anyone who had been prominent in party politics, particularly in the Republican camp. We preferred to have the Committee made up of liberals and Democrats, so that we would non be charged with having partisan motives."[67]

The Committee made a determined stand confronting the Judiciary nib. It distributed more than 15 one thousand thousand letters condemning the plan. They targeted specific constituencies: subcontract organization, editors of agricultural publications, and individual farmers. They besides distributed material to 161,000 lawyers, 121,000 doctors, 68,000 business leaders, and 137,000 clergymen. Pamphleteering, press releases and trenchantly worded radio editorials condemning the bill also formed part of the onslaught in the public loonshit.[68]

Firm activity [edit]

Traditionally, legislation proposed by the administration first goes before the Business firm of Representatives.[69] However, Roosevelt failed to consult Congressional leaders before announcing the bill, which stopped common cold any chance of passing the bill in the Firm.[69] House Judiciary Committee chairman Hatton Westward. Sumners believed the bill to be unconstitutional and refused to endorse it, actively chopping it upward within his committee in society to cake the legislation's primary effect of Supreme Court expansion.[69] [14] Finding such stiff opposition inside the House, the administration bundled for the bill to be taken up in the Senate.[69]

Congressional Republicans deftly decided to remain silent on the matter, denying congressional Democrats the opportunity to use them as a unifying force.[lxx] Republicans then watched from the sidelines equally the Autonomous political party split itself in the ensuing Senate fight.

Senate hearings [edit]

Senate Majority Leader Joseph T. Robinson. Entrusted by President Roosevelt with the court reform bill's passage, his unexpected death doomed the proposed legislation.

The administration began making its case for the nib before the Senate Judiciary Committee on March 10, 1937. Attorney Full general Cummings' testimony was grounded on four basic complaints:

- the reckless use of injunctions by the courts to pre-empt the functioning of New Bargain legislation;

- aged and infirm judges who declined to retire;

- crowded dockets at all levels of the federal court system; and

- the need for a reform which would infuse "new blood" in the federal court system.[71]

Administration advisor Robert H. Jackson testified next, attacking the Supreme Court'southward declared misuse of judicial review and the ideological perspective of the majority.[71] Further administration witnesses were grilled by the commission, so much then that later ii weeks less than half the administration'south witnesses had been chosen.[71] Exasperated by the stall tactics they were coming together on the committee, administration officials decided to call no further witnesses; it later proved to be a tactical corrigendum, allowing the opposition to indefinitely elevate-on the commission hearings.[71] Farther setbacks for the administration occurred in the failure of subcontract and labor interests to align with the administration.[72]

Withal, once the bill'due south opposition had gained the floor, it pressed its upper hand, continuing hearings every bit long as public sentiment confronting the bill remained in doubt.[73] Of note for the opposition was the testimony of Harvard University law professor Erwin Griswold.[74] Specifically attacked by Griswold's testimony was the claim made by the administration that Roosevelt'south court expansion program had precedent in U.S. history and law.[74] While it was true the size of the Supreme Court had been expanded since the founding in 1789, it had never been done for reasons similar to Roosevelt'due south.[74] The following table lists all the expansions of the court:

| Year | Size | Enacting legislation | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1789 | half dozen | Judiciary Act of 1789 | Original court with Principal Justice & five associate justices; two justices for each of the three excursion courts. (1 Stat. 73) |

| 1801 | five | Judiciary Act of 1801 | Lame duck Federalists, at end of President John Adams's administration, greatly aggrandize federal courts, but reduce the number of acquaintance justices¹ to iv in order to boss the judiciary and hinder judicial appointments by incoming President Thomas Jefferson.[75] (2 Stat. 89) |

| 1802 | 6 | Judiciary Act of 1802 | Democratic-Republicans repeal the Judiciary Act of 1801. Equally no vacancy had occurred in the interim, no seat on the court was e'er actually abolished. (ii Stat. 132) |

| 1807 | seven | Seventh Excursion Act | Created a new circuit courtroom for Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee; Jefferson appoints the new associate justice. (2 Stat. 420) |

| 1837 | 9 | Eighth & Ninth Circuits Act | Signed by President Andrew Jackson on his final full day in office; Jackson nominates two associate justices, both confirmed; one declines appointment. New President Martin Van Buren so appoints the second. (five Stat. 176) |

| 1863 | 10 | Tenth Circuit Human activity | Created Tenth Circuit to serve California and Oregon; added associate justice to serve information technology. (12 Stat. 794) |

| 1866 | 7 | Judicial Circuits Deed | Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase lobbied for this reduction.¹ The Radical Republican Congress took the occasion to overhaul the courts to reduce the influence of former Confederate States. (14 Stat. 209) |

| 1869 | 9 | Judiciary Act of 1869 | Ready Court at current size, reduced brunt of riding circuit by introducing intermediary circuit courtroom justices. (16 Stat. 44) |

| Notes | |||

| i. Because federal justices serve during "skilful behavior", reductions in a federal court's size are accomplished but through either abolishing the court or attrition—i.east., a seat is abolished merely when it becomes vacant. However, the Supreme Courtroom cannot exist abolished by ordinary legislation. As such, the actual size of the Supreme Court during a wrinkle may remain larger than the law provides until well after that law's enactment. | |||

Another event dissentious to the administration's case was a alphabetic character authored by Principal Justice Hughes to Senator Burton Wheeler, which straight contradicted Roosevelt's merits of an overworked Supreme Court turning down over 85 percentage of certiorari petitions in an endeavor to keep up with their docket.[76] The truth of the matter, according to Hughes, was that rejections typically resulted from the lacking nature of the petition, not from the courtroom's docket load.[76]

White Monday [edit]

On March 29, 1937, the court handed downwardly iii decisions upholding New Deal legislation, two of them unanimous: West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish,[10] Wright five. Vinton Branch,[77] and Virginia Railway v. Federation.[78] [79] The Wright case upheld a new Frazier-Lemke Act which had been redrafted to meet the Court's objections in the Radford example; similarly, Virginia Railway case upheld labor regulations for the railroad industry, and is particularly notable for its foreshadowing of how the Wagner Act cases would be decided equally the National Labor Relations Board was modeled on the Railway Labor Deed contested in the instance.[79]

Failure of reform legislation [edit]

Van Devanter retires [edit]

May 18, 1937 witnessed two setbacks for the assistants. First, Associate Justice Willis Van Devanter—encouraged by the restoration of full-salary pensions under the March 1, 1937[lxxx] [81] [82] Supreme Court Retirement Act[83] (Public Law 75-10; Chapter 21 of the full general statutes enacted in the 1st Session of the 75th Congress)—announced his intent to retire on June 2, 1937, the stop of the term.[84]

This undercut 1 of Roosevelt's chief complaints against the court—he had not been given an opportunity in the entirety of his first term to make a nomination to the high court.[84] It also presented Roosevelt with a personal dilemma: he had already long ago promised the first court vacancy to Senate Majority Leader Joseph T. Robinson.[84] As Roosevelt had based his attack of the court upon the ages of the justices, appointing the 65-year-old Robinson would belie Roosevelt's stated goal of infusing the court with younger blood.[85] Further, Roosevelt worried nearly whether Robinson could exist trusted on the high bench; while Robinson was considered to be Roosevelt's New Bargain "marshal" and was regarded as a progressive of the stripe of Woodrow Wilson,[86] [87] he was a conservative on some issues.[85] Withal, Robinson's death six weeks later eradicated this problem. Finally, Van Devanter's retirement alleviated pressure to reconstitute a more politically friendly court.

Committee report [edit]

The second setback occurred in the Senate Judiciary Committee activeness that day on Roosevelt's court reform nib.[88] First, an attempt at a compromise amendment which would take allowed the creation of but two boosted seats was defeated 10–8.[88] Next, a motion to report the neb favorably to the floor of the Senate besides failed 10–8.[88] Then, a motion to written report the beak "without recommendation" failed past the aforementioned margin, 10–8.[88] Finally, a vote was taken to report the pecker adversely, which passed 10–8.[88]

On June fourteen, the commission issued a scathing report that called FDR's plan "a needless, futile and utterly dangerous abandonment of constitutional principle ... without precedent or justification".[89] [9]

Public back up for the programme was never very stiff and dissipated quickly in the backwash of these developments.[ citation needed ] [ verification needed ]

Floor debate [edit]

Entrusted with ensuring the nib'due south passage, Robinson began his attempt to go the votes necessary to pass the bill.[90] In the meantime, he worked to terminate another compromise which would abate Democratic opposition to the bill.[91] Ultimately devised was the Hatch-Logan subpoena, which resembled Roosevelt'due south plan, but with changes in some details: the age limit for appointing a new coadjutor was increased to 75, and appointments of such a nature were limited to one per calendar year.[91]

The Senate opened debate on the substitute proposal on July two.[92] Robinson led the charge, holding the floor for two days.[93] Procedural measures were used to limit debate and prevent any potential delay.[93] By July 12, Robinson had begun to show signs of strain, leaving the Senate chamber complaining of chest pains.[93]

On July 14, 1937 a housemaid plant Joseph Robinson expressionless of a heart attack in his flat, the Congressional Record at his side.[93] With Robinson gone and then too were all hopes of the bill's passage.[94] Roosevelt farther alienated his political party's Senators when he decided not to attend Robinson'southward funeral in Fiddling Stone, Arkansas.[95]

On returning to Washington, D.C., Vice President John Nance Garner informed Roosevelt, "You are beat. You lot haven't got the votes."[96] On July 22, the Senate voted 70–20 to transport the judicial-reform measure back to commission, where the controversial linguistic communication was stripped by explicit pedagogy from the Senate floor.[97]

By July 29, 1937, the Senate Judiciary Committee—at the bidding of new Senate Bulk Leader Alben Barkley—had produced a revised Judicial Procedures Reform Human action.[98] This new legislation met with the previous bill's goal of revising the lower courts, but without providing for new federal judges or justices.

Congress passed the revised legislation, and Roosevelt signed it into police, on August 26.[99] This new constabulary required that:

- parties-at-conform provide early observe to the federal government of cases with constitutional implications;

- federal courts grant government attorneys the right to appear in such cases;

- appeals in such cases be expedited to the Supreme Court;

- any constitutional injunction would no longer exist enforced by one federal judge, just rather iii; and

- such injunctions would be limited to a sixty-twenty-four hour period elapsing.[98]

Consequences [edit]

A political fight which began as a conflict between the President and the Supreme Court turned into a battle between Roosevelt and the recalcitrant members of his ain party in the Congress.[16] The political consequences were broad-reaching, extending across the narrow question of judicial reform to implicate the political future of the New Deal itself. Non only was bipartisan support for Roosevelt's agenda largely dissipated past the struggle, the overall loss of political capital letter in the loonshit of public stance was too significant.[16] The Democratic Party lost a internet of eight seats in the U.S. Senate and a net 81 seats in the U.S. Firm in the subsequent 1938 midterm elections.

Equally Michael Parrish writes, "the protracted legislative boxing over the Courtroom-packing pecker blunted the momentum for additional reforms, divided the New Deal coalition, squandered the political advantage Roosevelt had gained in the 1936 elections, and gave fresh ammunition to those who defendant him of dictatorship, tyranny, and fascism. When the dust settled, FDR had suffered a humiliating political defeat at the hands of Chief Justice Hughes and the administration's Congressional opponents."[100] [101]

With the retirement of Justice Willis Van Devanter in 1937, the Courtroom's composition began to motion in support of Roosevelt's legislative agenda. Past the end of 1941, following the deaths of Justices Benjamin Cardozo (1938) and Pierce Butler (1939), and the retirements of George Sutherland (1938), Louis Brandeis (1939), James Clark McReynolds (1941), and Charles Evans Hughes (1941), only two Justices (quondam Associate Justice, by then promoted to Master Justice, Harlan Fiske Stone, and Associate Justice Owen Roberts) remained from the Court Roosevelt inherited in 1933.

Equally time to come Chief Justice William Rehnquist observed:

President Roosevelt lost the Courtroom-packing boxing, only he won the war for control of the Supreme Court ... not by any novel legislation, but by serving in function for more than than twelve years, and appointing viii of the nine Justices of the Court. In this mode the Constitution provides for ultimate responsibility of the Court to the political branches of regime. [Withal] information technology was the Us Senate—a political torso if in that location ever was one—who stepped in and saved the independence of the judiciary ... in Franklin Roosevelt's Court-packing plan in 1937.[102]

Timeline [edit]

| Twelvemonth | Engagement | Case | Cite | Vote | Holding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | |||||

| 1934 | Jan 8 | Home Building & Loan Association v. Blaisdell | 290 U.Due south. 398 (1934) | 5–four | Minnesota's interruption of creditor'due south remedies constitutional |

| Mar 5 | Nebbia v. New York | 291 U.Due south. 502 (1934) | 5–4 | New York's regulation of milk prices constitutional | |

| 1935 | Jan seven | Panama Refining Co. 5. Ryan | 293 U.S. 388 (1935) | 8–1 | National Industrial Recovery Act, §9(c) unconstitutional |

| Feb eighteen | Norman v. Baltimore & Ohio R. Co. | 294 U.S. 240 (1935) | 5–iv | Gold Clause Cases: Congressional abrogation of contractual gold payment clauses ramble | |

| Nortz v. Usa | 294 U.S. 317 (1935) | v–4 | |||

| Perry five. U.s.a. | 294 U.S. 330 (1935) | 5–4 | |||

| May six | Railroad Retirement Bd. five. Alton R. Co. | 295 U.S. 330 (1935) | five–four | Railroad Retirement Human activity unconstitutional | |

| May 27 | Schechter Poultry Corp. 5. U.s. | 295 U.S. 495 (1935) | nine–0 | National Industrial Recovery Act unconstitutional | |

| Louisville Joint Stock Land Bank five. Radford | 295 U.Southward. 555 (1935) | 9–0 | Frazier-Lemke Act unconstitutional | ||

| Humphrey's Executor v. United states of america | 295 U.Due south. 602 (1935) | 9–0 | The President may not remove any appointee to an independent regulatory agency except for reasons that Congress has provided by law. | ||

| 1936 | January 6 | United States v. Butler | 297 U.S. 1 (1936) | 6–3 | Agricultural Adjustment Human action unconstitutional |

| Feb 17 | Ashwander v. TVA | 297 U.S. 288 (1936) | eight–1 | Tennessee Valley Say-so ramble | |

| Apr 6 | Jones v. SEC | 298 U.Due south. ane (1936) | 6–3 | SEC rebuked for "Star Chamber" abuses | |

| May 18 | Carter five. Carter Coal Company | 298 U.Due south. 238 (1936) | v–four | Bituminous Coal Conservation Human action of 1935 unconstitutional | |

| May 25 | Ashton v. Cameron County Water Improvement Dist. No. 1 | 298 U.Due south. 513 (1936) | 5–4 | Municipal Defalcation Human activity of 1934 ruled unconstitutional | |

| June i | Morehead five. New York ex rel. Tipaldo | 298 U.S. 587 (1936) | 5–4 | New York'southward minimum wage police force unconstitutional | |

| Nov three | Roosevelt electoral landslide | ||||

| Dec xvi | Oral arguments heard on W Coast Hotel Co. five. Parrish | ||||

| Dec 17 | Associate Justice Owen Roberts indicates his vote to overturn Adkins v. Children's Hospital, upholding Washington state'due south minimum wage statute contested in Parrish | ||||

| 1937 | Feb 5 | Final briefing vote on W Coast Hotel | |||

| Judicial Procedures Reform Nib of 1937 ("JPRB37") announced | |||||

| February 8 | Supreme Courtroom begins hearing oral arguments on Wagner Human action cases | ||||

| Mar 9 | "Fireside chat" regarding national reaction to JPRB37 | ||||

| Mar 29 | Due west Coast Hotel Co. five. Parrish | 300 U.South. 379 (1937) | 5–4 | Washington country's minimum wage law constitutional | |

| Wright v. Vinton Branch | 300 U.S. 440 (1937) | ix–0 | New Frazier-Lemke Act ramble | ||

| Virginian Railway Co. five. Railway Employees | 300 U.S. 515 (1937) | 9–0 | Railway Labor Act constitutional | ||

| Apr 12 | NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp. | 301 U.S. ane (1937) | 5–4 | National Labor Relations Deed constitutional | |

| NLRB v. Fruehauf Trailer Co. | 301 U.Due south. 49 (1937) | 5–4 | |||

| NLRB v. Friedman-Harry Marks Clothing Co. | 301 U.S. 58 (1937) | v–iv | |||

| Associated Press v. NLRB | 301 U.S. 103 (1937) | v–4 | |||

| Washington Jitney Co. v. NLRB | 301 U.S. 142 (1937) | 5–iv | |||

| May xviii | "Horseman" Willis Van Devanter announces his intent to retire | ||||

| May 24 | Steward Motorcar Company v. Davis | 301 U.Due south. 548 (1937) | five–4 | Social Security taxation constitutional | |

| Helvering 5. Davis | 301 U.Southward. 619 (1937) | 7–2 | |||

| Jun 2 | Van Devanter retires | ||||

| Jul fourteen | Senate Majority Leader Joseph T. Robinson dies | ||||

| Jul 22 | JPRB37 referred back to committee by a vote of seventy–20 to strip "court packing" provisions | ||||

| Aug 19 | Senator Hugo Blackness sworn in as Associate Justice | ||||

Encounter likewise [edit]

- Second-term curse

- Terminate Court-Packing Act

References [edit]

Notes [edit]

- ^ Parrish, Michael E. (2002). The Hughes Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Inc. p. 24. ISBN9781576071977 . Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ a b Epstein, at 451.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 115ff.

- ^ Sean J. Savage (1991). Roosevelt, the Party Leader, 1932–1945. University Printing of Kentucky. p. 33. ISBN978-0-8131-1755-iii.

- ^ a b "Ashurst, Defeated, Reviews Service". The New York Times. September 12, 1940. p. 18.

- ^ Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum (December eleven, 2015). "Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Supreme Court". Presidential Timeline of the National Archives and Records Assistants. Presidential Libraries of the National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on December 6, 2015.

- ^ "Fireside Conversation (March nine, 1937)". The American Presidency Projection.

- ^ Winfield, Betty (1990). FDR and the news media. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. p. 104. ISBN0-252-01672-6.

- ^ a b c Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Reorganization of the Federal Judiciary, Due south. Rep. No. 711, 75th Congress, 1st Session, 1 (1937).

- ^ a b 300 U.South. 379 (1937)

- ^ White, at 308.

- ^ McKenna, at 413.

- ^ Baker, Richard Allan (1999). "Ashurst, Henry Fountain". In Garraty, John A.; Carnes, Mark C. (eds.). American National Biography. Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 686–687. ISBN0-xix-512780-three.

- ^ a b "TSHA | Court-Packing Plan of 1937".

- ^ Ryfe, David Michael (1999). "Franklin Roosevelt and the fireside chats". The Journal of Communication. 49 (4): fourscore–103 [98–99]. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1999.tb02818.x. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Leuchtenburg, at 156–161.

- ^ Epstein, at 440.

- ^ Oliver Wendell Holmes: law and the inner self, K. Edward White pg. 469

- ^ McKenna, at 35–36, 335–36.

- ^ a b McKenna, at xx–21.

- ^ a b c d McKenna, at 24–25.

- ^ McKenna, at xiv–16.

- ^ Schlesinger, at 261.

- ^ Jenson, Carol Eastward. (1992). "New Deal". In Hall, Kermit L. (ed.). Oxford Companion to the United states Supreme Court. Oxford University Printing.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, William E. (June 2005). "Charles Evans Hughes: The Center Holds". North Carolina Law Review. 83: 1187–1204.

- ^ a b c White, at 167–70.

- ^ 252 U.South. 416 (1920)

- ^ Gillman, Howard (2000). "Living Constitution". Macmillan Reference United states. Retrieved Jan 28, 2009.

- ^ White, at 204–05.

- ^ a b c Cushman, at 5–7.

- ^ White, at 158–163.

- ^ a b c White, at 203–04.

- ^ a b Leuchtenburg, at 84.

- ^ 290 U.S. 398 (1934)

- ^ 291 U.S. 502 (1934)

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 26.

- ^ Nebbia v. New York , 291 U.Southward. 502, 524 (1934).

- ^ a b McKenna, at 96–103.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved February v, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create every bit title (link) - ^ Urofsky, at 681–83.

- ^ a b c Leuchtenburg, at 83–85.

- ^ McKenna, at 146.

- ^ a b c d McKenna, at 157–68.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 94.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 98.

- ^ McKenna, at 169.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 110.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 118–19.

- ^ Annual Written report of the Attorney General (Washington, D.C.: 1913), 10.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 120.

- ^ McKenna, at 296.

- ^ McReynolds, James Clark Archived May 14, 2009, at the Wayback Automobile, Federal Judicial Heart, visited January 28, 2009.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 124.

- ^ Frederick, David C. (1994). Rugged Justice: The Ninth Circuit Courtroom of Appeals and the American Due west, 1891-1941. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 181. ISBN0-520-08381-four.

Before long, Denman had championed the cosmos of additional Ninth Circuit judgeships and reform of the entire federal judicial organisation. In testimony earlier Congress, speeches to bar groups, and letters to the president, Denman worked tirelessly to create an administrative office for the federal courts, to add fifty new district judges and eight new circuit judges nationwide, and to end unnecessary delays in litigation. Denman's zeal for administrative reform, combined with the deeply divergent views amid the judges on the legality of the New Deal, gave the internal workings of the 9th Circuit a much more political imprimatur than it had had in its start four decades.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 113–14; McKenna, at 155–157.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 125.

- ^ a b c Leuchtenburg, at 129.

- ^ Perry, Barbara; Abraham, Henry (2004). "Franklin Roosevelt and the Supreme Court: A New Deal and a New Epitome". In Shaw, Stephen Chiliad.; Pederson, William D.; Williams, Frank J. (eds.). Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Transformation of the Supreme Court. London: M.Due east. Sharpe. pp. 13–35. ISBN0-7656-1032-9 . Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Kammen, Michael G. (2006). A Machine that Would Become of Itself: The Constitution in American Culture. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. pp. 8–ix, 276–281. ISBN1-4128-0583-X.

- ^ a b "Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary". Fireside Chats. Episode 9. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. March nine, 1937.

- ^ Caldeira, Gregory A. (December 1987). "Public Stance and The U.Southward. Supreme Court: FDR's Court-Packing Plan". The American Political Science Review. 81 (4): 1139–1153. doi:ten.2307/1962582. JSTOR 1962582.

- ^ Caldeira, 1146–47

- ^ McKenna, at 303–314.

- ^ McKenna, at 285.

- ^ Hinshaw, David (2005). A Man from Kansas: The Story of William Allen White. Whitefish, Montana: Kessinger Publishing. pp. 258–259. ISBNi-4179-8348-5.

- ^ Richard Polenberg, "The National Committee to Uphold Constitutional Government, 1937–1941", The Journal of American History, Vol. 52, No. three (1965-12), at 582–598.

- ^ Frank Gannett, "History of the Formation of the N.C.U.C.G. and the Supreme Court Fight", August 1937, Frank Gannett Papers, Box xvi (Collection of Regional History, Cornell University). Cited in Polenburg at 583.

- ^ Polenberg, at 586.

- ^ a b c d McKenna, at 314–317.

- ^ McKenna, at 320–324.

- ^ a b c d McKenna, at 356–65.

- ^ McKenna, at 381.

- ^ McKenna, at 386–96.

- ^ a b c McKenna, at 396–401.

- ^ May, Christopher Northward.; Ides, Allan (2007). Constitutional Law: National Power and Federalism (4th ed.). New York: Aspen Publishers. p. eight.

- ^ a b McKenna, at 367–372.

- ^ 300 U.S. 440 (1937)

- ^ 300 U.S. 515 (1937)

- ^ a b McKenna, at 420–22.

- ^ "New Bargain Timeline (text version)".

- ^ Columbia Law Review, Vol. 37, No. vii (Nov., 1937). pg. 1212

- ^ "Schlesinger v. Reservists Commission to Stop the State of war 418 U.S. 208". (1974)

- ^ Brawl, Howard. Hugo Fifty. Black: Cold Steel Warrior. Oxford Academy Press. 2006. ISBN 0-19-507814-four. Page 89.

- ^ a b c McKenna, at 453–57.

- ^ a b McKenna, at 458.

- ^ "Joseph Taylor Robinson (1872–1937) - Encyclopedia of Arkansas". www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Civilization (EOA).

- ^ "People Leaders Robinson".

- ^ a b c d e McKenna, at 460–61.

- ^ McKenna, at 480–87.

- ^ McKenna, at 319.

- ^ a b McKenna, at 486–91.

- ^ McKenna, at 496.

- ^ a b c d McKenna, at 498–505.

- ^ McKenna, at 505.

- ^ McKenna, at 515.

- ^ McKenna, at 516.

- ^ McKenna, at 519–21.

- ^ a b Black, Conrad (2003). Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Champion of Freedom. New York: PublicAffairs. p. 417. ISBN978-1-58648-184-one.

- ^ Pederson, William D. (2006). Presidential Profiles: The FDR Years. New York: Facts on File, Inc. p. 284. ISBN9780816074600 . Retrieved Oct 31, 2013.

- ^ Parrish, Michael (1983). "The Great Depression, the New Bargain, and the American Legal Order". Washington Constabulary Review. 59: 737.

- ^ McKenna, at 522ff.

- ^ Rehnquist, William H. (2004). "Judicial Independence Dedicated to Chief Justice Harry Fifty. Carrico: Symposium Remarks". Academy of Richmond Constabulary Review. 38: 579–596 [595].

Sources [edit]

- Baker, Leonard (1967). Back to Back: The Duel Between FDR and the Supreme Courtroom . New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Caldeira, Gregory A. (December 1987). "Public Opinion and The U.South. Supreme Court: FDR's Court-Packing Programme". The American Political Scientific discipline Review. 81 (4): 1139–1153. doi:10.2307/1962582. JSTOR 1962582.

- Cushman, Barry (1998). Rethinking the New Bargain Courtroom: The Structure of a Ramble Revolution. New York, NY: Oxford Academy Printing. ISBN978-0-xix-511532-one.

- Epstein, Lee; Walker, Thomas G. (2007). Constitutional Law for a Irresolute America: Institutional Powers and Constraints (6th ed.). Washington, D.C.: CQ Printing. ISBN978-1-933116-81-v.

- Leuchtenburg, William E. (1995). The Supreme Court Reborn: The Constitutional Revolution in the Age of Roosevelt . New York, NY: Oxford Academy Press. ISBN978-0-nineteen-511131-6.

- McKenna, Marian C. (2002). Franklin Roosevelt and the Cracking Constitutional State of war: The Court-packing Crisis of 1937. New York, NY: Fordham University Press. ISBN978-0-8232-2154-vii.

- Minton, Sherman Reorganization of Federal Judiciary; speeches of Hon. Sherman Minton of Indiana in the Senate of the United States, July 8 and 9, 1937. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1937.

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. (2003). The Politics of Upheaval: the Age of Roosevelt, 1935–1936 . Vol. 3. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN978-0-618-34087-3.

- Shaw, Stephen K.; Pederson, William D.; Williams, Frank J., eds. (2004). Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Transformation of the Supreme Court. London: K.E. Sharpe. ISBN0-7656-1032-9.

- Urofsky, Melvin I.; Finkelman, Paul (2002). A March of Liberty: A Constitutional History of the United States . Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Printing. ISBN978-0-19-512637-2.

- White, G. Edward (2000). The Constitution and the New Bargain. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN978-0-674-00831-1.

External links [edit]

- FDR'southward Fireside Chat on the pecker

- 1990 Eyewitness Account of Law Clerk Joseph L. Rauh, Jr. (Link alive as of September xv, 2008)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judicial_Procedures_Reform_Bill_of_1937

Posted by: backlundyouggedge.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Did Franklin D Roosevelt Try To Change The Makeup Of The Supreme Court"

Post a Comment